By SUZANNE VEGA

In the last few months I have had a chance to review a song I wrote in October of 2007. It’s called “Daddy Is White,” and I haven’t sung it out loud yet in front of an audience except to record a demo of it. My daughter worries that people might make fun of me. However, I feel that it is a truthful song.

In my last blog post I mentioned that I was raised in a half-Puerto Rican family and spent five years in East Harlem as a young child. At some point, when I was about 9 years old, I learned that my birth father was actually English-Scottish-Irish. Or white, as we used to say in my old neighborhood. Actually, anybody looking at me could probably tell that this was the case, but I felt I was the last to know, partly because I was treated by my Puerto Rican abuelita and my aunt and uncle as one of their own. I was proud, and still am proud, to be a Vega.

One person wrote in after my last blog entry to ask whether I had any plans to record Puerto Rican songs or songs in Spanish as a way of honoring those roots. I thought about this, but have to say no, even though I have had experience singing songs in Spanish. One of my first performing jobs was with a group called The Alliance of Latin Arts. I was 15 years old, and it was a government sponsored job, where we traveled from borough to borough singing songs in Spanish, like “La Bamba.” I attracted attention wherever I went, and it wasn’t because of my singing. (Somewhere in storage in a folder marked “scrapbook” I have a flyer from that job — when I find it I will post it here.) If you could look at the photo, you would see one girl in the line of dark-skinned Latinas to the far right looking down, and that is me, sticking out as usual.

It always struck me that in this picture I look like I am not only of a different race, but of a different century, as though I were Emily Dickinson and had somehow wandered into the Bronx in the 1970’s. (It should be noted that Puerto Ricans are not of one race — there are blue-eyed blond Puerto Ricans, though I never actually met any until recently.) I feel it would be false of me to do an album of Puerto Rican songs, since pretending I fit in, even back then, always felt a bit forced.

Songs brand us a part of a tribe. We can pick and choose what tribe we belong to. Goth, emo, hippie, punk, folk, alternative, for example. “Mom! Why are you wearing all black?” my daughter recently shouted at me. “You look so emo!” “I always wear black,” I mumbled. “But we are at the beach!” she said. Well, maybe she had a point.

I am of Irish descent, among other things, but I feel it would be false of me to perform traditional Irish music, even though I find some of it very moving. When I worked with Mitchell Froom, I liked that he said, “I will reveal you to be the mutant you really are!” when he heard how I grew up and about the mixed bag of stuff I grew up listening to — from Woody Guthrie and Phil Ochs to Motown, Lou Reed, Leonard Cohen and Bob Dylan. But perhaps one day I could do an album of Jewish folk songs in A-minor, or an album of cante jondo, which Federico Garcia Lorca wrote of; this would take guts. I love sad and tragic songs, and I love the sensuality of Brazilian bossa nova; perhaps my melancholic temperament could do justice to an album like this.

I remember walking down the street one day, wearing a Smiths t-shirt, back in the mid-’80s. I was headed for the subway station, and I had to pass through a crowd of black teenagers to get there. There were maybe eight or so young men, looking me up and down as I picked my way through them. My neck prickled with worry. What would they say? Would they call me a goofy white girl, or worse?

One of them snickered. My stomach dropped. Then another one sang out, “I am human and I need to be loved!! Just like everybody else does!!” Morrissey’s transcendental lyrics from “How Soon Is Now?” It was so unexpected that I burst out laughing. They knew the song! Then we all laughed, and the tension was broken. Maybe we were the same tribe after all.

* * *

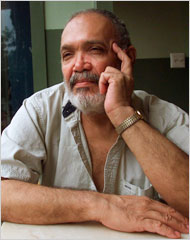

Ed Vega, circa 1972.

This song is called “Daddy Is White,” and I don’t know what tribe it represents. Maybe you also thought your daddy was Puerto Rican, and then you turned out to have another father! The song doesn’t even apply to my brothers and sister, whose daddy really was Ed Vega, who is shown here at the dining room table with the family guitar. However, the second and third verses were also drawn from reality — the second verse applies to the neighborhood I live in, where if you walk anywhere you run into the projects, where you can still feel those prickles, and feel all eyes on you: “What is she doing here?”

In the weeks following the recent election, though, there has been a very different feeling in the air in these neighborhoods, a feeling of relief, of recognition, of pride. There is going to be a man in the White House (Barack Obama) whose mother was white and whose father was black. He was a mixed-race child; he is a black man. His family is multicultural, as mine is. What a relief to see this represented in the realities of power and politics! In the media!

We say these words out loud and in print. Black, white. When I recorded the demo of this song earlier this year my engineer and I discussed what the song was about. At one point I realized we were whispering those words. Now we say them out loud, and they reflect our reality. It matters.

The last verse was inspired by a real-life discussion I overheard at a bar in Baltimore. A black man and a white woman were discussing a recent sports event. He called her “baby” playfully. She called him “stats boy,” meaning, I guess, someone well-versed in statistics. The conversation escalated quickly into a loud yelling argument, as he did not feel he was a boy of any kind and that word had racist overtones. Maybe the recent election means my song is on its way to being obsolete. I hope so.

Daddy Is White (By Suzanne Vega, 2007)

I am an average white girl who comes from Upper Manhattan.

And I am totally white, but I was raised half Latin.

This caused me some problems among my friends and my foes,

Cause when you look into my face, it’s clear what everybody else knows:

Chorus:

My daddy is white.

So I must be white too.

When you look into the mirror, what

Comes looking back at you?

If your daddy is white,

You must be white too.

When you look into the mirror

what comes looking back at you?

I feel it in the city when I take a walk uptown

I feel the tension in the air, I feel it ticking all around,

I feel it filling up the sidewalk, in the spaces in between,

Between my face and your face in public places where we get seen.

Chorus

He called her baby. She called him boy, and then it started.

They were strangers at the bar, and they both ended broken hearted.

And it was a conversation, but it ended as a fight.

And I can tell you it’s because he was black, and she was white.