NYC Councilwoman Melissa Mark Viverito invites you to

“Hon. Sonia Sotomayor Confirmation Hearings”

An Informational Meeting

Monday, July 13 at 11:30am – 2:30pm

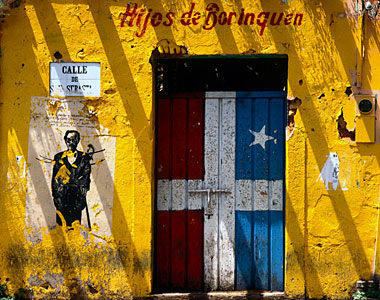

Camaradas El Barrio

2241 First Avenue @ 115th Street

NYC

NYC Councilwoman Melissa Mark Viverito invites you to

“Hon. Sonia Sotomayor Confirmation Hearings”

An Informational Meeting

Monday, July 13 at 11:30am – 2:30pm

Camaradas El Barrio

2241 First Avenue @ 115th Street

NYC

por Wilfredo Rojas

Community Focus/Enfoque Comunal (23 de julio 2009)

Segun informacion recibida de la capital de Washington, DC, la juez Sonia Sotomayor, va en camino a convertirse en el primer miembro latino de la Corte Suprema de Estados Unidos. La juez gano el apoyo del Comite Judicial del senado este pasado lunes con un voto de 13 a 6 para enviar su recomendacion al senado competo, que se espera que confirme su nombramiento al alto tribunal.

En otros aconcientimientos, este domingo 23 de agosto a las 12 de medio dia muchos de los jovenes que compusieron el movimiento de lo que fue el partido los Young Lords estaran celebrando un encuentro en la Primera Iglesia Metodista Hispana en las calle 111 y avenida Lexington en la ciudad de Nueva York. Miembros de esta organizacion que lucho por los derechos de los latinos en los anos 60’s y 70’s tomaron posesion de esta casa de adoracion dos veces para establecer programas de ayuda para los pobres del barrio de Spanish Harlem. El encuentro contara con la participacion del pastor Santos, la congregacion y los ahora maduro miembros de los Young Lords.

Ya hacen cuarenta andos desde que la presencia de los Young Lords tomo la delantera en la lucha por los derechos de los puertorriquenos en particular, los latinos en general y las minorias de este pais en total. Un grupo que empezo como una ganga callerjera en la ciudad de Chicago se convertio en una fuerza politica popular en la ciudad de Nueva York y se movio a establecer capitolos atraves de las mayores ciudades de Estados Unidos con grandes concentraciones de boricuas. La organizacion nacionalista revolucionaria puertorriquena lucho para la igualdad, las reindivicaciones inmediatas, asi como la definicion del estatus de Puerto Rico. La rama de Filadelfia era una de las mas activas en la nacion y produjo muchos logros para una comunidad que abiertamente era subjecta a ataques raciales y la discriminacion abierto en aquellos anos.

Aunque los Young Lords ya no existen en los Estados Unidos, muchos de sus miembros si siguen la lucha para mejorar las condiciones para un pueblo puertorriqueno/latino que aun sigue segun podemos ver en la batalla para defender lo suyo y echar a sus hijos palante en una sociedad que cuenta con mas caras latinas segun pasan los anos. Estos jovenes que sacrificaron tanto para que hoy se respete un poco mas al latino establecieron un movimiento que encendio el orgullo de la herencia hispana en la juventud de hoy dia.

El Cuarenta Aniversario de la fundacion de los Young Young Lords contara con varias actividad que se estaran llevando a cabo tanto en Nueva York como aqui en Filadelfia y otras ciudades. Se invitan a esas personas que fueron miembros o simpatizantes de los Young Lords en sus anos a que se comuniquen conmigo al 267-718-3266 si les interesa viajar al encuentro en Nueva York o tiene interes en participar en alguna de las actividades organizada para marca este perodio historico en la vida de la comunidad latina de la nacion.

Si hoy estamos cerca de lograr la primera jueza hispana a la Corte Suprema se debe a grupos como los Young Lords que nunca bajaron la guardia y empujaron para lograr mas oportunidades y igualdad para los hispanos en este pais norteamericano.

Wilfredo P. Rojas es columnista del semanario bilingüe Community Focus/Enfoque Comunal de Filadelfia. Es fundador y fue parte del liderato de la rama de Filadefia de los Young Lords. Hoy es director de la Oficina de Justicia y Ayuda Communal de los Sistemas de Prisones de Filadelfia.

The Senate votes 68 to 31 to confirm Sotomayor, who will be the first Latino and third woman ever on the nation’s highest court. Nine Republicans cross party line to support her confirmation.

By James Oliphant and David G. Savage

Los Angeles Times (August 6, 2009)

Reporting from Washington – Sonia Sotomayor completed an unlikely and historic journey today, one that began with her birth in a Bronx, New York, housing project 55 years ago and culminated in her confirmation as the Supreme Court’s 111th justice.

When she is sworn into office, Sotomayor will take her place as the high court’s first Latino and just its third woman. She was approved by a 68-31 Senate vote after three days of debate. Nine Republicans crossed party lines to support her.

Sotomayor was nominated in May by President Obama to replace retiring Justice David H. Souter. A judge on the U.S. 2nd Circuit Court of Appeals for the last 11 years, Sotomayor worked her way through two Ivy League schools and was a Manhattan prosecutor and corporate lawyer before joining the federal bench.

But the pride felt by Latino groups over her historic nomination quickly gave way to a firestorm, as critics seized upon a speech Sotomayor gave to a group of students in 2001. Sotomayor suggested that her life experience as a Latina shaped her judging, and her remarks became known, almost notoriously, as the “wise Latina” speech.

Sotomayor’s opponents charged that the speech and some of her decisions on the bench showed an inclination to use the law to favor disadvantaged minority groups. And they pointed to one case in particular — in which Sotomayor’s appellate court panel threw out a discrimination suit brought by white firefighters in New Haven, Conn. — as evidence of their claim.

But the controversy never appeared to seriously threaten her nomination.

With Democrats in control of the Senate, there was little possibility of a Republican-led filibuster. And Sotomayor’s supporters pointed to thousands of opinions in her long judicial career, few if any of which showed the sort of liberal-leaning that her detractors alleged existed.

Over three long days of confirmation hearings, Sotomayor pledged “fidelity to the law” and rejected the “empathy standard” that Obama invoked when the Supreme Court vacancy arose. The president had said that justices need to sometimes utilize empathy to understand the effect the court’s decisions have on the lives of ordinary Americans. But Sotomayor broke with Obama over that notion, a moment her conservative critics said was particularly significant.

Still, most Republicans weren’t mollified — and during this week’s debate, they said they doubted Sotomayor’s ability to remain impartial on the bench.

“This is a question of the true role of the judge. It is a question of whether a judge follows the law as it is written or how they wish it should be,” Sen. Jeff Sessions of Alabama, the top Republican on the Judiciary Committee, said shortly before today’s vote.

But Sen. Patrick J. Leahy of Vermont, chairman of the committee that oversaw Sotomayor’s nomination, said on the Senate floor that the judge had answered her critics and proved her suitability for the court. He called on Republicans to support the nominee to honor “our national promise.”

“Judge Sotomayor’s career and judicial record demonstrates that she has always followed the rule of law,” Leahy said. “Attempts at distorting that record by suggesting that her ethnicity or heritage will be the driving force in her decisions as a justice of the Supreme Court are demeaning to women and all communities of color.”

By DAVID GONZALEZ

New York Times (August 6, 2009)

In the summer of 1959, Edwin Torres landed a $60-a-week job and wound up on the front page of El Diario. He had just been hired as the first Puerto Rican assistant district attorney in New York – and probably, he thinks, the entire United States.

He still recalls the headline: “Exemplary Son of El Barrio Becomes Prosecutor.”

“You would’ve thought I had been named attorney general,” he said. “That’s how big it was.”

Half a century later, the long and sometimes bittersweet history of Puerto Ricans in New York is expected to add a celebratory chapter today as the Senate confirms Judge Sonia Sotomayor’s nomination to the Supreme Court. Her personal journey – from a single-parent home in the South Bronx projects to the Ivy League and an impressive legal career – has provoked a fierce pride in many other Puerto Ricans who glimpse reflections of their own struggles.

“This is about the acceptance that eluded us,” said Mr. Torres, 78, who himself earned distinction as a jurist, novelist and raconteur. “It is beyond anybody’s imagination when I started that a Puerto Rican could ascend to that position, to the Supreme Court.”

Arguably the highest rung that any Puerto Rican has yet reached in this country, the nomination of Judge Sotomayor is a watershed event for Puerto Rican New York. It builds on the achievements that others of her generation have made in business, politics, the arts and pop culture. It extends the legacy of an earlier, lesser-known generation who created social service and educational institutions that persist today, helping newcomers from Mexico and the Dominican Republic.

Yet the city has also been a place of heartbreak. Though Puerto Ricans were granted citizenship in 1917 and large numbers of them arrived in New York in the 1950s, poverty and lack of opportunity still pockmark some of their neighborhoods. A 2004 report by a Hispanic advocacy group showed that compared with other Latino groups nationwide, Puerto Ricans had the highest poverty rate, the lowest average family income and the highest unemployment rate for men.

In politics, the trailblazer Herman Badillo saw his career go from a series of heady firsts in the 1960s to frustration in the 1980s when his dreams of becoming the city’s first Puerto Rican mayor were foiled by Harlem’s political bosses. Just four years ago, Fernando Ferrer was trounced in his bid against Mayor Michael R. Bloomberg.

All those setbacks lose their sting, if only for a moment, in the glow of Judge Sotomayor’s achievement, which many of her fellow Puerto Ricans say is as monumental for them as President Obama’s victory was for African-Americans. It has affirmed a sense of Puerto Rican identity at a moment when that distinction is often obscured by catch-all labels like Latino and Hispanic – and even as it is subjected to negative comparisons.

“Many elite Latin Americans have implied that Puerto Ricans blew it, because we had citizenship and did nothing,” said Lillian Jimenez, a documentary filmmaker who co-produced a series of television ads in support of Judge Sotomayor’s nomination. “But we were the biggest Spanish-speaking group in New York for decades, and bore the brunt of discrimination, especially in the 1950s. We struggled for our rights. We have people everywhere doing all kinds of things. But that history has not been known.”

That history is in danger of disappearing in East Harlem, long the cradle of Puerto Rican New York. After waves of gentrification and development, parts of the area are now being advertised as Upper Yorkville, a new annex to the predominantly white Upper East Side. While the poor have stayed behind, many of East Harlem’s successful sons and daughters have scattered to the suburbs.

“We have a whole intellectual and professional class that is invisible – people who came up though the neighborhood, with a working-class background, who really excelled,” said Angelo Falcon, president of the National Institute for Latino Policy.

“But it’s so dispersed, people don’t see it. They do not make up a real, physical community, but they have the identity.”

For those who paved the way for Judge Sotomayor, embracing that identity was the first step in charting their personal and professional paths out of hardship. Manuel del Valle, 60, an overachiever from the housing projects on Amsterdam Avenue, made the same leaps as the judge – to Princeton University and Yale Law School – but preceded her by five years.

Taking a cue from the black students at Princeton, he and the handful of working-class Puerto Ricans from New York pressured university officials to offer a course on Puerto Rican history and to admit more minority students. They saw their goal as creating a class of lawyers, doctors, writers and activists who would use their expertise to lift up their old neighborhoods.

“Talk about arrogance,” said Mr. del Valle, who now teaches law in Puerto Rico. “We actually believed we would have a dynamic impact on all the institutions American society had to offer.”

Judge Sotomayor’s nomination, he said, is a vindication of those efforts.

“We were invisible,” he said. “She made us visible.”

In New York, many have welcomed the judge’s visibility during a summer when the most celebrated – and reviled – local politicians were two Puerto Rican state senators who brought the state government to a standstill by mounting an abortive coup against their fellow Democrats.

“She really came at a moment when there is a public reassessment of the value of identity politics through this brouhaha in the Senate,” said Ms. Davila, a professor of anthropology at New York University who has written extensively on Puerto Rican and Latino identity. “Here came this woman who reinvigorated us with the idea that a Latina can have a lot to contribute, not just to their own group, but to the entire American society.”

But it is among her own – in the South Bronx, East Harlem or the Los Sures neighborhood of Brooklyn – where Judge Sotomayor’s success resonates loudest, for the simple reason that many people understand the level of perseverance she needed to achieve it.

Orlando Plaza, 41, who took time off from his doctoral studies in history about five years ago to open Camaradas, a popular bar in East Harlem, sees her appeal as a sort of ethnic Rorschach test.

“Whether it’s growing up in the Bronx, going to Catholic school or being from a single-parent household, there are so many tropes in her own story that we feel pride that someone from a background like ours achieved something so enormous,” he said. “This is the real Jenny from the block.”

And it is on the block, among the men and women who left Puerto Rico decades ago so their children might one day become professionals, where her story is most sweetly savored. The faces of the men and women playing dominoes or shooting pool at the Betances Senior Center in the Bronx attest to decades of hard work.

Many of them came to New York as teenagers more out of despair than dreams. Lucy Medina, who arrived in the 1950s, worked as a keypunch operator and in other jobs as she singlehandedly raised two children. Today, her son is a captain in the city’s Department of Correction and her daughter is a real estate executive.

Impressive as the judge’s accomplishments are, Ms. Medina is more impressed with the judge’s mother, Celina Sotomayor, who did what she had to do in order to raise two successful children in the projects.

“Her mother and I are very similar,” said Ms. Medina, 77. “I know what she went through. We sacrificed ourselves so our children would get an education and get ahead. A lot of women here have done that. We stayed on top of our children and made sure they didn’t get sidetracked.”

Wednesday, June 10th 2009, 9:33 AM, Daily News Blog

Among the many stereotypes about Latinos perpetuated by popular culture is that of the so-called “Latin temper.” Since Lupe Vélez exploded on the screen as “The Mexican Spitfire” in the 1930s, Latinos, particularly women, have been depicted as having an uncontrollable, fiery temperament, a short fuse that at the slightest provocation makes us rant and rave in rapid-fire Spanish.

In the 1950s, a decade tone-deaf to cultural differences, throwing a tantrum or just having a run-of-the-mill ataque de nervios was diagnosed as the “Puerto Rican Syndrome” or “Puerto Rican Hysteria.” This curious illness, first detected by the military among Puerto Rican soldiers during the Korean War to identify what today is called posttraumatic disorder or battlefield trauma, had been discredited for years. Now it’s back, with a strange twist.

As soon as it was announced that a Puerto Rican woman was nominated to the Supreme Court of the United States, a breakout of “Puerto Rican Hysteria” spread like wildfire around cable news studios and other mainstream media outlets.

However, the people now convulsing and foaming at the mouth are not Puerto Rican at all. They are middle-aged conservative white males.

The Mouthzilla Brigade (Rush Limbaugh, Pat Buchanan, Sean Hannity, Glenn Beck) and the Four Has-beens of the Apocalypse (Newt Gingrich, Tom Tancredo, Karl Rove and G. Gordon Liddy) have centered their attack of nerves on Judge Sonia Sotomayor’s alleged lack of “judicial temperament” while being quite discombobulated themselves.

Republican elected officials had, for the most part, taken their Prozac and kept their peace. Then, last Wednesday, during her courtesy calls to various senators, Judge Sotomayor stopped by to greet Sen. Lindsey Graham, Republican of South Carolina. After the meeting, Graham told reporters that he will not vote for Sotomayor because although she has the intellect and the credentials, she has “a temperament problem.”

What the heck does that mean? What happened during the half hour they spent behind closed doors? Did her Latin blood boil over, driving her to poke him in the eye with a loop earring? Did she whack him on the head with a pair of maracas?

The temperament charge stems from the fact that Sotomayor is known as an assertive courtroom manager who keeps a tight rein on the proceedings and has little patience with dawdling lawyers — something that in a male judge is seen as a virtue.

But what really got the Mouthzillas and the Apocalipticos in a tizzy was Sotomayor’s decontextualized quote about a “wise Latina” making better decisions than a “white male.”

Charges of “reverse racism” flew, a respected Latino organization was compared to the KKK, and whining about how white men are discriminated against filled the air waves. And while this craziness went on, how have hot-tempered Latinos behaved? Like a model of coolness and restraint, shinning examples of dignity and respect. That’s because, unlike those aggrieved white males, we have years and years of experience in being disrespected and really discriminated against and even murdered for just being who we are. One stereotype down, 50 to go? Have we lost our pasión edge? Or are we just being muzzled?

Conspiracy theories abound. Perhaps all this Latino cool-headedness may be just a mirage, a made-for-television toned down response.

The fact is that in hundreds of mainstream media prime-time hours devoted to “reverse racism,” “affirmative action promotions” and “identity politics” vis a vis Judge Sotomayor, very few Latino faces and voices have been included in the discussions. So, what we actually think or feel about this issue, and many others, continues to be one of those eternally unknown mysteries of the universe. One way or another, let’s hope that we all come out of this distasteful national nervous breakdown a little wiser. After all, when in search of wisdom, there’s nothing like walking a mile in somebody else’s shoes.

doloresprida@aol.com

Read more: http://www.nydailynews.com/latino/columnists/prida/index.html#ixzz0IUe5gjES&C

The following is the text of the Judge Mario G. Olmos Memorial Lecture in 2001, delivered at the University of California, Berkeley, School of Law, by appeals court judge Sonia Sotomayor. It was published in the Spring 2002 issue of Berkeley La Raza Law Journal, a symposium issue entitled “Raising the Bar: Latino and Latina Presence in the Judiciary and the Struggle for Representation,” and it is reproduced here with permission from the journal.

“A Latina Judge’s Voice”

By Sonia Sotomayor

Judge Reynoso, thank you for that lovely introduction. I am humbled to be speaking behind a man who has contributed so much to the Hispanic community. I am also grateful to have such kind words said about me.

I am delighted to be here. It is nice to escape my hometown for just a little bit. It is also nice to say hello to old friends who are in the audience, to rekindle contact with old acquaintances and to make new friends among those of you in the audience. It is particularly heart warming to me to be attending a conference to which I was invited by a Latina law school friend, Rachel Moran, who is now an accomplished and widely respected legal scholar. I warn Latinos in this room: Latinas are making a lot of progress in the old-boy network.

I am also deeply honored to have been asked to deliver the annual Judge Mario G. Olmos lecture. I am joining a remarkable group of prior speakers who have given this lecture. I hope what I speak about today continues to promote the legacy of that man whose commitment to public service and abiding dedication to promoting equality and justice for all people inspired this memorial lecture and the conference that will follow. I thank Judge Olmos’ widow Mary Louise’s family, her son and the judge’s many friends for hosting me. And for the privilege you have bestowed on me in honoring the memory of a very special person. If I and the many people of this conference can accomplish a fraction of what Judge Olmos did in his short but extraordinary life we and our respective communities will be infinitely better.

I intend tonight to touch upon the themes that this conference will be discussing this weekend and to talk to you about my Latina identity, where it came from, and the influence I perceive it has on my presence on the bench.

Who am I? I am a “Newyorkrican.” For those of you on the West Coast who do not know what that term means: I am a born and bred New Yorker of Puerto Rican-born parents who came to the states during World War II.

Like many other immigrants to this great land, my parents came because of poverty and to attempt to find and secure a better life for themselves and the family that they hoped to have. They largely succeeded. For that, my brother and I are very grateful. The story of that success is what made me and what makes me the Latina that I am. The Latina side of my identity was forged and closely nurtured by my family through our shared experiences and traditions.

For me, a very special part of my being Latina is the mucho platos de arroz, gandules y pernil – rice, beans and pork – that I have eaten at countless family holidays and special events. My Latina identity also includes, because of my particularly adventurous taste buds, morcilla, — pig intestines, patitas de cerdo con garbanzo — pigs’ feet with beans, and la lengua y orejas de cuchifrito, pigs’ tongue and ears. I bet the Mexican-Americans in this room are thinking that Puerto Ricans have unusual food tastes. Some of us, like me, do. Part of my Latina identity is the sound of merengue at all our family parties and the heart wrenching Spanish love songs that we enjoy. It is the memory of Saturday afternoon at the movies with my aunt and cousins watching Cantinflas, who is not Puerto Rican, but who was an icon Spanish comedian on par with Abbot and Costello of my generation. My Latina soul was nourished as I visited and played at my grandmother’s house with my cousins and extended family. They were my friends as I grew up. Being a Latina child was watching the adults playing dominos on Saturday night and us kids playing loteria, bingo, with my grandmother calling out the numbers which we marked on our cards with chick peas.

Now, does any one of these things make me a Latina? Obviously not because each of our Carribean and Latin American communities has their own unique food and different traditions at the holidays. I only learned about tacos in college from my Mexican-American roommate. Being a Latina in America also does not mean speaking Spanish. I happen to speak it fairly well. But my brother, only three years younger, like too many of us educated here, barely speaks it. Most of us born and bred here, speak it very poorly.

If I had pursued my career in my undergraduate history major, I would likely provide you with a very academic description of what being a Latino or Latina means. For example, I could define Latinos as those peoples and cultures populated or colonized by Spain who maintained or adopted Spanish or Spanish Creole as their language of communication. You can tell that I have been very well educated. That antiseptic description however, does not really explain the appeal of morcilla – pig’s intestine – to an American born child. It does not provide an adequate explanation of why individuals like us, many of whom are born in this completely different American culture, still identify so strongly with those communities in which our parents were born and raised.

America has a deeply confused image of itself that is in perpetual tension. We are a nation that takes pride in our ethnic diversity, recognizing its importance in shaping our society and in adding richness to its existence. Yet, we simultaneously insist that we can and must function and live in a race and color-blind way that ignore these very differences that in other contexts we laud. That tension between “the melting pot and the salad bowl” — a recently popular metaphor used to described New York’s diversity – is being hotly debated today in national discussions about affirmative action. Many of us struggle with this tension and attempt to maintain and promote our cultural and ethnic identities in a society that is often ambivalent about how to deal with its differences. In this time of great debate we must remember that it is not political struggles that create a Latino or Latina identity. I became a Latina by the way I love and the way I live my life. My family showed me by their example how wonderful and vibrant life is and how wonderful and magical it is to have a Latina soul. They taught me to love being a Puertorriqueña and to love America and value its lesson that great things could be achieved if one works hard for it. But achieving success here is no easy accomplishment for Latinos or Latinas, and although that struggle did not and does not create a Latina identity, it does inspire how I live my life.

I was born in the year 1954. That year was the fateful year in which Brown v. Board of Education was decided. When I was eight, in 1961, the first Latino, the wonderful Judge Reynaldo Garza, was appointed to the federal bench, an event we are celebrating at this conference. When I finished law school in 1979, there were no women judges on the Supreme Court or on the highest court of my home state, New York. There was then only one Afro-American Supreme Court Justice and then and now no Latino or Latina justices on our highest court. Now in the last twenty plus years of my professional life, I have seen a quantum leap in the representation of women and Latinos in the legal profession and particularly in the judiciary. In addition to the appointment of the first female United States Attorney General, Janet Reno, we have seen the appointment of two female justices to the Supreme Court and two female justices to the New York Court of Appeals, the highest court of my home state. One of those judges is the Chief Judge and the other is a Puerto Riqueña, like I am. As of today, women sit on the highest courts of almost all of the states and of the territories, including Puerto Rico. One Supreme Court, that of Minnesota, had a majority of women justices for a period of time.

As of September 1, 2001, the federal judiciary consisting of Supreme, Circuit and District Court Judges was about 22% women. In 1992, nearly ten years ago, when I was first appointed a District Court Judge, the percentage of women in the total federal judiciary was only 13%. Now, the growth of Latino representation is somewhat less favorable. As of today we have, as I noted earlier, no Supreme Court justices, and we have only 10 out of 147 active Circuit Court judges and 30 out of 587 active district court judges. Those numbers are grossly below our proportion of the population. As recently as 1965, however, the federal bench had only three women serving and only one Latino judge. So changes are happening, although in some areas, very slowly. These figures and appointments are heartwarming. Nevertheless, much still remains to happen.

Let us not forget that between the appointments of Justice Sandra Day O’Connor in 1981 and Justice Ginsburg in 1992, eleven years passed. Similarly, between Justice Kaye’s initial appointment as an Associate Judge to the New York Court of Appeals in 1983, and Justice Ciparick’s appointment in 1993, ten years elapsed. Almost nine years later, we are waiting for a third appointment of a woman to both the Supreme Court and the New York Court of Appeals and of a second minority, male or female, preferably Hispanic, to the Supreme Court. In 1992 when I joined the bench, there were still two out of 13 circuit courts and about 53 out of 92 district courts in which no women sat. At the beginning of September of 2001, there are women sitting in all 13 circuit courts. The First, Fifth, Eighth and Federal Circuits each have only one female judge, however, out of a combined total number of 48 judges. There are still nearly 37 district courts with no women judges at all. For women of color the statistics are more sobering. As of September 20, 1998, of the then 195 circuit court judges only two were African-American women and two Hispanic women. Of the 641 district court judges only twelve were African-American women and eleven Hispanic women. African-American women comprise only 1.56% of the federal judiciary and Hispanic-American women comprise only 1%. No African-American, male or female, sits today on the Fourth or Federal circuits. And no Hispanics, male or female, sit on the Fourth, Sixth, Seventh, Eighth, District of Columbia or Federal Circuits.

Sort of shocking, isn’t it? This is the year 2002. We have a long way to go. Unfortunately, there are some very deep storm warnings we must keep in mind. In at least the last five years the majority of nominated judges the Senate delayed more than one year before confirming or never confirming were women or minorities. I need not remind this audience that Judge Paez of your home Circuit, the Ninth Circuit, has had the dubious distinction of having had his confirmation delayed the longest in Senate history. These figures demonstrate that there is a real and continuing need for Latino and Latina organizations and community groups throughout the country to exist and to continue their efforts of promoting women and men of all colors in their pursuit for equality in the judicial system.

This weekend’s conference, illustrated by its name, is bound to examine issues that I hope will identify the efforts and solutions that will assist our communities. The focus of my speech tonight, however, is not about the struggle to get us where we are and where we need to go but instead to discuss with you what it all will mean to have more women and people of color on the bench. The statistics I have been talking about provide a base from which to discuss a question which one of my former colleagues on the Southern District bench, Judge Miriam Cederbaum, raised when speaking about women on the federal bench. Her question was: What do the history and statistics mean? In her speech, Judge Cederbaum expressed her belief that the number of women and by direct inference people of color on the bench, was still statistically insignificant and that therefore we could not draw valid scientific conclusions from the acts of so few people over such a short period of time. Yet, we do have women and people of color in more significant numbers on the bench and no one can or should ignore pondering what that will mean or not mean in the development of the law. Now, I cannot and do not claim this issue as personally my own. In recent years there has been an explosion of research and writing in this area. On one of the panels tomorrow, you will hear the Latino perspective in this debate.

For those of you interested in the gender perspective on this issue, I commend to you a wonderful compilation of articles published on the subject in Vol. 77 of the Judicature, the Journal of the American Judicature Society of November-December 1993. It is on Westlaw/Lexis and I assume the students and academics in this room can find it.

Now Judge Cedarbaum expresses concern with any analysis of women and presumably again people of color on the bench, which begins and presumably ends with the conclusion that women or minorities are different from men generally. She sees danger in presuming that judging should be gender or anything else based. She rightly points out that the perception of the differences between men and women is what led to many paternalistic laws and to the denial to women of the right to vote because we were described then “as not capable of reasoning or thinking logically” but instead of “acting intuitively.” I am quoting adjectives that were bandied around famously during the suffragettes’ movement.

While recognizing the potential effect of individual experiences on perception, Judge Cedarbaum nevertheless believes that judges must transcend their personal sympathies and prejudices and aspire to achieve a greater degree of fairness and integrity based on the reason of law. Although I agree with and attempt to work toward Judge Cedarbaum’s aspiration, I wonder whether achieving that goal is possible in all or even in most cases. And I wonder whether by ignoring our differences as women or men of color we do a disservice both to the law and society. Whatever the reasons why we may have different perspectives, either as some theorists suggest because of our cultural experiences or as others postulate because we have basic differences in logic and reasoning, are in many respects a small part of a larger practical question we as women and minority judges in society in general must address. I accept the thesis of a law school classmate, Professor Steven Carter of Yale Law School, in his affirmative action book that in any group of human beings there is a diversity of opinion because there is both a diversity of experiences and of thought. Thus, as noted by another Yale Law School Professor — I did graduate from there and I am not really biased except that they seem to be doing a lot of writing in that area – Professor Judith Resnik says that there is not a single voice of feminism, not a feminist approach but many who are exploring the possible ways of being that are distinct from those structured in a world dominated by the power and words of men. Thus, feminist theories of judging are in the midst of creation and are not and perhaps will never aspire to be as solidified as the established legal doctrines of judging can sometimes appear to be.

That same point can be made with respect to people of color. No one person, judge or nominee will speak in a female or people of color voice. I need not remind you that Justice Clarence Thomas represents a part but not the whole of African-American thought on many subjects. Yet, because I accept the proposition that, as Judge Resnik describes it, “to judge is an exercise of power” and because as, another former law school classmate, Professor Martha Minnow of Harvard Law School, states “there is no objective stance but only a series of perspectives – no neutrality, no escape from choice in judging,” I further accept that our experiences as women and people of color affect our decisions. The aspiration to impartiality is just that–it’s an aspiration because it denies the fact that we are by our experiences making different choices than others. Not all women or people of color, in all or some circumstances or indeed in any particular case or circumstance but enough people of color in enough cases, will make a difference in the process of judging. The Minnesota Supreme Court has given an example of this. As reported by Judge Patricia Wald formerly of the D.C. Circuit Court, three women on the Minnesota Court with two men dissenting agreed to grant a protective order against a father’s visitation rights when the father abused his child. The Judicature Journal has at least two excellent studies on how women on the courts of appeal and state supreme courts have tended to vote more often than their male counterpart to uphold women’s claims in sex discrimination cases and criminal defendants’ claims in search and seizure cases. As recognized by legal scholars, whatever the reason, not one woman or person of color in any one position but as a group we will have an effect on the development of the law and on judging.

In our private conversations, Judge Cedarbaum has pointed out to me that seminal decisions in race and sex discrimination cases have come from Supreme Courts composed exclusively of white males. I agree that this is significant but I also choose to emphasize that the people who argued those cases before the Supreme Court which changed the legal landscape ultimately were largely people of color and women. I recall that Justice Thurgood Marshall, Judge Connie Baker Motley, the first black woman appointed to the federal bench, and others of the NAACP argued Brown v. Board of Education. Similarly, Justice Ginsburg, with other women attorneys, was instrumental in advocating and convincing the Court that equality of work required equality in terms and conditions of employment.

Whether born from experience or inherent physiological or cultural differences, a possibility I abhor less or discount less than my colleague Judge Cedarbaum, our gender and national origins may and will make a difference in our judging. Justice O’Connor has often been cited as saying that a wise old man and wise old woman will reach the same conclusion in deciding cases. I am not so sure Justice O’Connor is the author of that line since Professor Resnik attributes that line to Supreme Court Justice Coyle. I am also not so sure that I agree with the statement. First, as Professor Martha Minnow has noted, there can never be a universal definition of wise. Second, I would hope that a wise Latina woman with the richness of her experiences would more often than not reach a better conclusion than a white male who hasn’t lived that life.

Let us not forget that wise men like Oliver Wendell Holmes and Justice Cardozo voted on cases which upheld both sex and race discrimination in our society. Until 1972, no Supreme Court case ever upheld the claim of a woman in a gender discrimination case. I, like Professor Carter, believe that we should not be so myopic as to believe that others of different experiences or backgrounds are incapable of understanding the values and needs of people from a different group. Many are so capable. As Judge Cedarbaum pointed out to me, nine white men on the Supreme Court in the past have done so on many occasions and on many issues including Brown.

However, to understand takes time and effort, something that not all people are willing to give. For others, their experiences limit their ability to understand the experiences of others. Other simply do not care. Hence, one must accept the proposition that a difference there will be by the presence of women and people of color on the bench. Personal experiences affect the facts that judges choose to see. My hope is that I will take the good from my experiences and extrapolate them further into areas with which I am unfamiliar. I simply do not know exactly what that difference will be in my judging. But I accept there will be some based on my gender and my Latina heritage.

I also hope that by raising the question today of what difference having more Latinos and Latinas on the bench will make will start your own evaluation. For people of color and women lawyers, what does and should being an ethnic minority mean in your lawyering? For men lawyers, what areas in your experiences and attitudes do you need to work on to make you capable of reaching those great moments of enlightenment which other men in different circumstances have been able to reach. For all of us, how do change the facts that in every task force study of gender and race bias in the courts, women and people of color, lawyers and judges alike, report in significantly higher percentages than white men that their gender and race has shaped their careers, from hiring, retention to promotion and that a statistically significant number of women and minority lawyers and judges, both alike, have experienced bias in the courtroom?

Each day on the bench I learn something new about the judicial process and about being a professional Latina woman in a world that sometimes looks at me with suspicion. I am reminded each day that I render decisions that affect people concretely and that I owe them constant and complete vigilance in checking my assumptions, presumptions and perspectives and ensuring that to the extent that my limited abilities and capabilities permit me, that I reevaluate them and change as circumstances and cases before me requires. I can and do aspire to be greater than the sum total of my experiences but I accept my limitations. I willingly accept that we who judge must not deny the differences resulting from experience and heritage but attempt, as the Supreme Court suggests, continuously to judge when those opinions, sympathies and prejudices are appropriate.

There is always a danger embedded in relative morality, but since judging is a series of choices that we must make, that I am forced to make, I hope that I can make them by informing myself on the questions I must not avoid asking and continuously pondering. We, I mean all of us in this room, must continue individually and in voices united in organizations that have supported this conference, to think about these questions and to figure out how we go about creating the opportunity for there to be more women and people of color on the bench so we can finally have statistically significant numbers to measure the differences we will and are making.

I am delighted to have been here tonight and extend once again my deepest gratitude to all of you for listening and letting me share my reflections on being a Latina voice on the bench. Thank you.

Below please find a reply I wrote to the recent article by “Black Agenda Report (BAR) the journal of African American political thought and action” on an article entitled “Sonia Sotomayor: She’s No Clarence Thomas, But No Thurgood Marshall Either” by managing editor Bruce A. Dixon. I invite all readers to write BAR and express your opinion on this important nomination. The article is on the following website: http://www.blackagendareport.com/

Black Agenda Report(BAR) Joins the Anti-Latino Sotomayor Agenda

By Howard Jordan

I was saddened to witness Black Agenda Report (BAR) join the chorus of attacks on Latina justice Sonia Sotomayor. The article “Sonia Sotomayor: She’s No Clarence Thomas, But No Thurgood Marshall Either” by managing editor Bruce A. Dixon trivializes the historic importance of the nomination of the first Latina to the court. It also does a disservice to the Puerto Rican/Latino legal and political experience in the United States. Let me address some the points you raise:

First you argue that corporate media is exaggerating the importance of the nomination and it just feeds the notion that anybody can overcome racism in America. As a New York born Puerto Rican/Latino the importance of the nomination to our community is unprecedented. Though racism is structural and will not be eliminated by one appointment Mr. Dixon the narrative is important. A diabetic Latina, who lost her father when she was nine, raised in a housing project speaking a foreign language, attended Princeton, was editor a Yale Law Review, and served on the bench for seventeen years is a tribute and recognition of the important contributions Latin@s have made to this nation. The elevation of Thurgood Marshal to the Supreme Court during that historical period received the same sense of elation in the African-American community. It is as one Dominican legislator noted a “Jackie Robinson moment” for the 40 million Latinos in the U.S.

I am troubled that in your article you make only a passing reference to the racist comments characterizing Sotomayor as a “reverse racist,” an “affirmative action pick, a Hispanic chick, making fun of her unpronounceable last name, or cartoon depictions of her strung up like a piñata with a sombrero as an “easy out for progressives…to waste all their time and oxygen debating Republicans, ridiculing and refuting their racism.” The Latino community, as do all communities of color, have a responsibility and yes even an obligation to refute unfounded attacks that stereotype Justice Sotomayor and by extension promote racist stereotypes against Latinos.

Second, you rightly note Justice Sotomayor’s participation on the Board of the Puerto Rican Legal Defense and Education Fund, the main civil rights law firm for Latinos in the Northeast, but demean that participation by referring to the fact that she was “reportedly involved.” You state “No reports we have seen say that she personally filed those suits or that she ever appeared in court on behalf of litigants in discrimination and other lawsuits… she can hardly claim sole credit for it. The best barometer of her participation in PRLDEF is the statement of Puerto Ricans themselves. As Cesar Perales, the PRLDEF President stated “Sonia displayed an increasing amount of leadership on the board.” Unless of course you are going to parrot the white right and argue that Perales is only saying that because he’s Puerto Rican. She served nobly. By the way as I am sure you know board members don’t bring the cases in civil rights organizations.

Mr. Dixon, Ms. Sotomayor was one of 20 Hispanics in her class at Princeton and co-chairwoman of the Puerto Rican organization Accion Puertorriqueno where she wrote a complaint accusing Princeton of discrimination and convinced the leaders of the Chicano Caucus to co-sign it and filed it with the federal Department of Health, Education and Welfare. As a result of her efforts, Princeton employed its first Hispanic administrator and invited a Puerto Rican professor to teach. (New York Times) Perhaps you also missed her Yale Law Review article where she urged the granting of special rights for off-shore mineral rights for Puerto Rico not enjoyed by U.S. states, a historical corollary to the Vieques struggle of the Puerto Rican nation. (New York Times-David Gonzalez)

The one point you raise that I wholeheartedly agree with is your recognition of the contributions of Justice Thurgood Marshal and his transformation of the legal and racial landscape. As an attorney Justice Marshal remains one of my heroes and is the most important Supreme Court justice in U.S. history. But I consider the Sotomayor nomination as part of the historical continuum of the Latino contribution to the broader struggle for civil rights. It is the cross fertilization of our communities struggle for legal equality.

For example, in the case of Mendez v. Westminster, nine years before Brown vs. the Board of Education, on March 2, 1945, five Latino fathers (Gonzalo Mendez, Thomas Estrada, William Guzman, Frank Palomino, and Lorenzo Ramirez) challenged the practice of school segregation in the Ninth Federal District Court in Los Angeles. They claimed that their children, along with 5,000 other children of “Mexican and Latin descent”, were victims of unconstitutional discrimination by being forced to attend separate “Mexican” schools in the Westminster, Garden Grove, Santa Ana, and El Modeno school districts of Orange County. Judge Paul J. McCormick ruled in favor of Mendez and his co-plaintiffs on February 18, 1946. As a result “separate but equal” ended in California schools and legally enforced separation of racial and national groups in the public education system. The governor of the state at this time was Earl Warren who later decided Brown.

I will not go on to cite all the contributions of Sotomayor this gifted jurist who is a legatee of our contributions to our struggle for social justice. Anybody with roots in our community understands this reality and can readily access her contributions through the internet or the written and oral histories of our community if they so desired.

Third, you maintain that her legal experience a “mere 12 years of legal experience” five as a prosecutor and 7 for and corporate firm is not significant. Perhaps in your analysis you failed to mention that Justice Sotomayor has more legal experience that any of the nominees on the present court had at the time. Even more troubling is your transparent attempts to cherry pick those cases that would present Justice Sotomayor in a negative pro-corporate light. As the New York Times indicated Justice Sotomayor would bring more federal judicial experience to the Supreme Court than any justice in 100 years and more overall judicial experience than anyone confirmed in the court in the past 70 years. She participated in over 3000 panel decisions and authored roughly 400 opinions.

Fourthly, you establish a false causal connection between the Rockefeller Drug laws and the development of the prison-industrial complex and Sotomayor. The article argues that during this period Sotomayor as a prosecutor did not inject herself in this scandalous imprisonment of people of color. I frankly don’t see the connection, did Sotomayor cause this situation? During this same historical period Puerto Ricans were held as Puerto Rican political prisoners in American prisons and many progressive lawyers did not speak out. Many jurist, liberals, and yes progressive of color have not played a leading role in denouncing the colonization of the Puerto Rican people (America’s last colony), despite the efforts of our people to bring our situation to the courts, yet I would not blame them for assisting the colonizers in their silence.

Five, you use a corporate news media source like the Wall Street Journal to argue that Justice Sotomayor not only represented corporate clients but rejoiced in that representation. You note that absent from the conversation is a cursory review of her (Sotomayor’s) legal career then proceed to offer your readers a less than cursory review of your own. I am particularly disturbed on how your article cherry picked the cases that pigeon hole the judge as pro-business- but conveniently ignored other decisions such as the 2006 case Merrill Lynch v. Dabit where she allowed class action lawsuits against Merrill Lynch or her ruling in favor of the players (workers) in the major league baseball strike. As many scholars have noted that her opinions do not necessarily put her in a pro- or anti-business camp. (New York Times-May 28)

It might also have been more intellectually honest to note the civil liberties decision by the Justice in the Ricci case allowing the city of New Haven to reject an exam that discriminated against African American and Latinos or her support against insensitive strip search of a 13 year old girl as intrusive. Or the case of United States v. Reimer where Judge Sotomayor wrote an opinion revoking the US citizenship for a man charged with working for the Nazis in World War II Poland, guarding concentration camps and helping empty the Jewish ghettos. And in Lin v. Gonzales where she ordered renewed consideration of the asylum claims of Chinese women who experienced or were threatened with forced birth control

I would add that while I would not reject the argument that many of the Justice’s experience have also been corporate friendly as is most of the court, I don’t believe we have any “revolutionaries” on the bench. Will the nomination of Sotomayor destroy the corporate state/capitalism or free people of color from the racial oppression in the United States- no but is it a significant step forward- yes.

I am particularly troubled with the overall tenor of your article characterizing Justice Sotomayor as a “zealot advocate for multinational business” and an “easy out for progressives around the Sotomayor nomination is to waste all their time and oxygen debating Republicans, ridiculing and refuting their racism.” I am a progressive and I wholeheartedly reject your advice. Justice Sotomayor is reflective of the Puerto Rican/Latino experience in the United States. I would submit to you Mr. Dixon that recognizing a community’s leadership is about “respect” and I view your article as disrespectful and a cavalier dismissal of our historical experience.

As a New York born Puerto Rican I have spent a large part of my life organizing in the Latino community and struggling to build bridges between Latinos and African Americans. From the struggles against police brutality, to the Jackson campaign in 1984 and 1988, to support for the election of Mayor Dinkins, to the endorsement of candidate Obama for the Presidency who received 67 percent of the Latino vote. It is in the interest of both African Americans and Latinos to continue to cement the historical alliance between our communities and against the white supremacy that has relegated both our communities to the bottom of the economic ladder. “Sticking it” to our leaders and refusing to recognize the different levels of our “racialization” of our respective communities does not lend itself to that goal. It instead diminishes solidarity, weakens alliances, and deprives our communities of the benefits of sharing experiences.

As a regular reader of BAR I have enormous appreciation for the insight your publication has on issues of importance to all communities of color. I have read with interest your critiques of President Obama and embrace of Rosa Clemente’s candidacy as the first Afro-Puerto Rican Vice-Presidential candidate for the Green Party. That is why I was bitterly disappointed at your blind spot on the importance of the nomination of Sotomayor as “historical milestone.” The first African American President nominating the first Latina to the U.S. Supreme Court is reflective of a new Black-Brown paradigm in America where all contributions are fully recognized. We must bring together the legacies of those “those who picked cotton and those that cut sugar cane.” However, with all due respect, this will not be accomplished by promoting anti-Latino sentiments in the mainstream press.

Howard Jordan, host

The Jordan Journal

WBAI-Pacifica

From the Culture Kitchen blog

I cannot understand the brouhaha in some circles on the left around Sonia Sotomayor’s description of her parents as “immigrants”. And I certainly cannot believe that people on the right are so petty as to not call her the first “Hipanic”/Latina to the Supreme Court by calling Benjamin Cardozo, a man of Portuguese ascendancy, “Hipanic”.

Many of my readers know how I feel about the word “Hispanic”, so let me put this to rest: The census document quoted in my infamous article expressely describes the word “Hipanic” as used by the agency to describe Puerto Rican and other Americans of Latin American origins who did fall into the category of Mexicans. Citizens of Spaniards and Portuguese backgrounds were not “Hipanics” because they were Europeans. Same with Spanish and Portuguese -speaking African and Asian immigrants.

So people, let’s lay this one to rest: Benjamin Cardozo is not a Hispanic or Latino. Period.

Yet let me get to the issue of whether Puerto Ricans can be called immigrants.

I am appalled that in some mailing lists used by liberal bloggers there’s a rush to accuse right-wing commentators and even Sonia Sotomayor herself for calling her parents “Puerto Rican immigrants”. The logic behind this? That since Puerto Rico is a colony of the United States where Puerto Ricans have US citizenship, that this invalidates calling Puerto Rico a “foreign country” and it’s people as “immigrants to the United States”. The fight is to accuse the right of smearing her parents with the word immigrants because Puerto Ricans, allegedly, have no immigrant experience.

And what baffles me most is that the people pushing this line of thinking are “immigration activists” for whom it is a nuisance to fit Puerto Ricans in their “comprehensive immigration reform” narrative. In the past few years all the talk of immigration laws has been about how it is used to attack Mexicans and other mostly Central Americans. Yet the reality is very different.

You may want to call Puerto Ricans “migrants” because they we live in a US territory, but the peculiar political status of Puerto Rico as a pseudo-“Free Associated State” (aka: Commonwealth) has made many define Puerto Rican identity in the United States as one of immigrants with no immigrant status.

Rene Marques’ La Carreta (the Oxcart) became in the middle of the 20th century “the play” that captured this migrant/immigrant ethos of the Puerto Rican experience. In the play, a family of sugar-cane field workers sets out of the plantation looking for a better life. They not only end in a slum when in San Juan, but their penury there pushes them to New York City, where they only find ruin, despair and a death that returns them to the land they had previously fled from.

The play became an allegory for Puerto Rican identity because it describes the Puerto Rican experience as one that is fundamentally migrant inside the island and immigrant when in the United States. Rene Marques’ neo-realist theater was cemented in history and in this case, in the historical context of Puerto Ricans being a nation of immigrants.

Many of the boricuas of the 20th century were descendants of immigrants themselves. Spain had given to many Europeans indentured labor contracts for settling in Puerto Rico back in the 19th Century. Through these contracts the King of Spain leased the land to whomever wanted to work it and buy it back with their revenues. Many non-Spanish speaking Spaniards ended in the country, especially Catalanes, Basques, Canarinos and Gallegos along with other European groups like Italians, Irish, along with Roma from many Eastern European countries. Even under Spanish rule Central land South Native Americans were imported as the preferred group of household servants for the Spanish elite.

Even though the task of defining what it was to be a Puerto Rican had been taken up by many artists and thinkers by the time Puerto Rico was invaded by the United States in 1898, the Puerto Rican criollo movement (aka, Spanish/European identified Puerto Ricans) was stronger and more influential than their nationalist counterparts and when compared to the separatist nationalist movement in Cuba and at the other corner of the fallen Spanish colonial world, the Philippines.

It explains in many ways why the United States furiously aligned themselves to these criollistas and unleashed a wave of violence against the mostly brown and black nationalist movement in Puerto Rico; even going as far as torturing the leader of the nationalist movement, Don Pedro Albizu Campos, by using him for radiation experiments.

Yet it’s Puerto Rico’s weird constitutional framework that muddles the migrant/immigrant debate. Here’s the preamble to the Constitution of the Commomwealth of Puerto Rico:

We, the people of Puerto Rico, in order to organize ourselves politically on a fully democratic basis, to promote the general welfare, and to secure for ourselves and our posterity the complete enjoyment of human rights, placing our trust in Almighty God, do ordain and establish this Constitution for the commonwealth which, in the exercise of our natural rights, we now create within our union with the United States of America.

In so doing, we declare:

The democratic system is fundamental to the life of the Puerto Rican community;

We understand that the democratic system of government is one in which the will of the people is the source of public power, the political order is subordinate to the rights of man, and the free participation of the citizen in collective decisions is assured;

We consider as determining factors in our life our citizenship of the United States of America and our aspiration continually to enrich our democratic heritage in the individual and collective enjoyment of its rights and privileges; our loyalty to the principles of the Federal Constitution; the co-existence in Puerto Rico of the two great cultures of the American Hemisphere; our fervor for education; our faith in justice; our devotion to the courageous, industrious, and peaceful way of life; our fidelity to individual human values above and beyond social position, racial differences, and economic interests; and our hope for a better world based on these principles.

I want to stop here a moment because there are no accidents with this preamble: At no point does it say that Puerto Ricans take an oath of loyalty to the United States. At no point does it say that Puerto Rico is part of the United States. On the contrary, this document goes through great pains in defining Puerto Rico as a separate nation and a separate country without acknowledging Puerto Ricans’ right to self-determination, autonomy and sovereignty. On the contrary, the nation of Puerto Rico and Puerto Ricans aspire continually to enrich our democratic heritage in the individual and collective enjoyment of of the rights and privileges that come with having US citizenship.

Can you understand why constitutionally many Puerto Ricans make the case that we are a nation recognized by the United States and thus a separate, albeit not foreign country?

And it’s this contradiction that defines the Puerto Rico experience in the United States. An experience that even though has been defined by US citizenship since 1917 (Puerto Ricans who emigrated between 1898 and 1917 to the US actually had PR passports), has always been one of emigration to the United States not just migration from the island.

So please, stop wasting time in debating whether it is OK to call Puerto Ricans immigrants. We are. Get over it. Now go and get Sonia Sotomayor confirmed to the Supreme Court.

Further Reading : Puerto Rico: A Colonial Experiment by Raymond Carr is an excellent resource and place to start reading about the development of the Puerto Rican commonwealth. So is Jose Trias Monge’s Puerto Rico: The Trials of the Oldest Colony in the World and Puerto Rico: A Political and Cultural History by Arturo Morales Carrion.

Use this url to link to this page