Minerva Gonzalez-Suvidad takes the time to think about her artwork in a variety of media and invites you to join her in this introspective solo show.

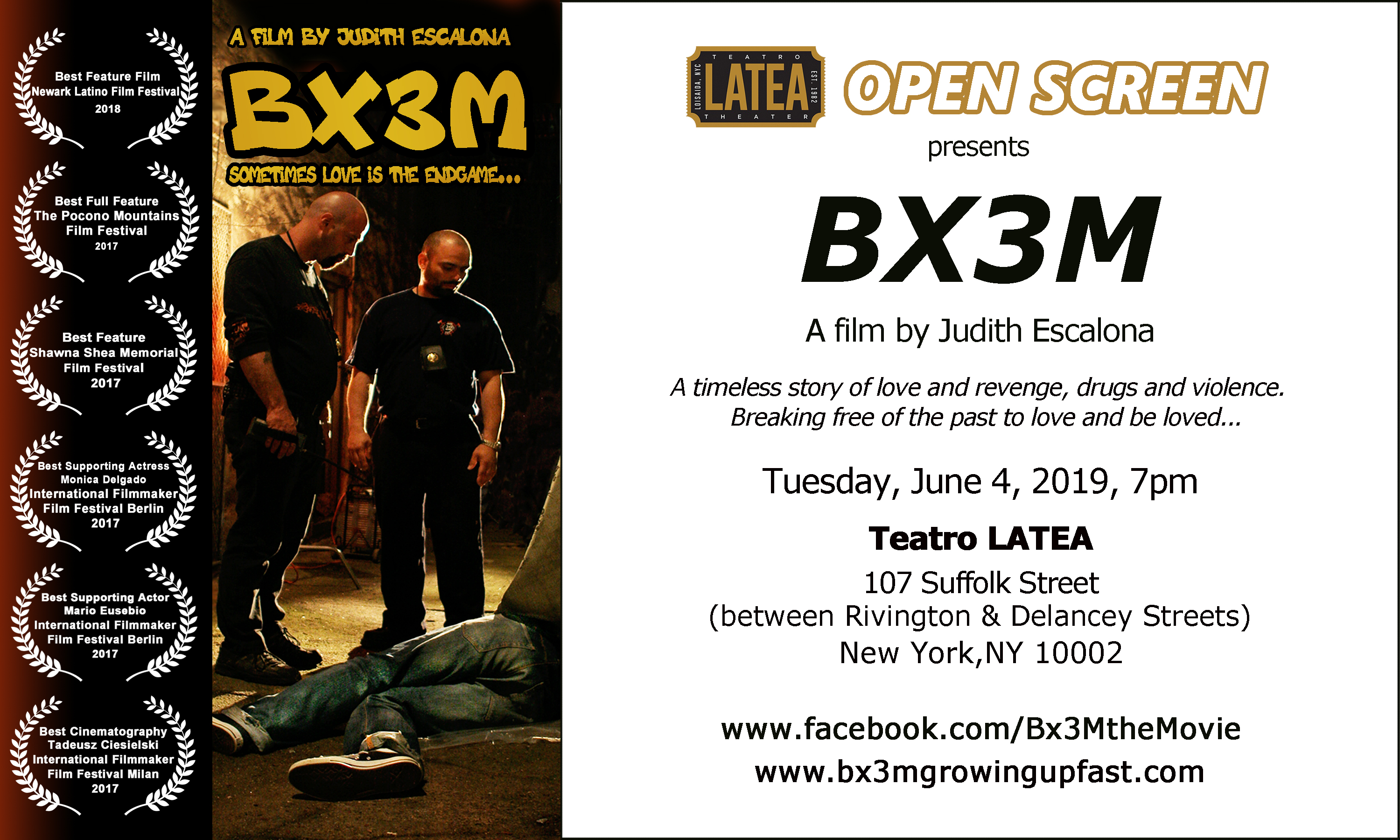

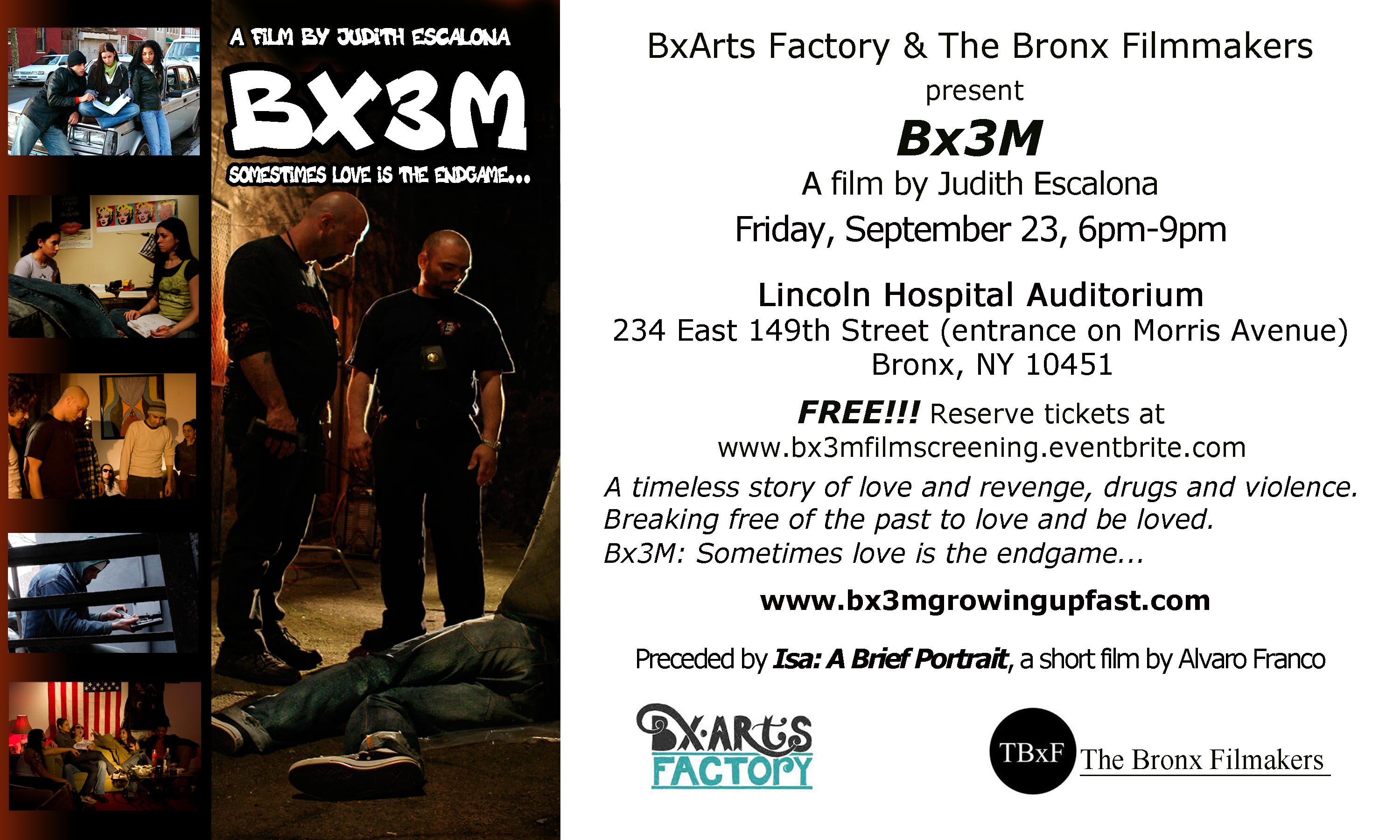

BX3M – Screening Tuesday, June 4, 2019, 7PM at Latea, 104 Suffolk Street

SUMMARY

For Maria and Mona, graduation means fulfilling a dream. For Michael, it means dashing all hope of a better future. You either make the grade or you don’t – in academics or love – and that makes all the difference.

Things are heating up as Maria, Mona and Michael get ready for their senior year at Monroe High in the Bronx. Maria is at the top of her class, but love is a subject she has yet to master. Mona wants to go to Cooper Union and that spells trouble for the aspiring photographer. Michael is flunking out. No matter, Michael is on a mission yet unknown to him— call it destiny or revenge.

A timeless story of love and revenge, drugs and violence… Breaking free of the past to love and be loved. BX3M: Sometimes love is the endgame.

FILMMAKER BIO

Judith Escalona grew up in the Bronx, where BX3M takes place, and returned home to make this feature. She previously wrote and directed The Krutch, a surreal narrative about a Puerto Rican psychoanalyst with an identity problem. She is currently working on a new screenplay for her next film.

A segment producer for CUNY-TV, Escalona is also the Founder and Executive Director of Puerto Rico and the American Dream (www.PRdream.com), the 21-year-old, award-winning website on the culture and art of the Puerto Rican diaspora. PRdream’s office was located in Spanish Harlem, where the organization launched several new media initiatives, among them the technology-based art gallery MediaNoche (http:// www.medianoche.us).

BX3M has garnered “Best Picture” awards from The Newark Latino Film Festiva 2018, Pocono Mountains Film Festival 2017, Shawna Shea Film Festival 2017. Escalona received three Communicator Awards 2012 for her work at CUNY-TV. She won First Prize in the Best Video category of the Ippies Awards 2011. New York State Senator Bill Perkins recognized her for her work in the arts. Judith Escalona received an Appreciation Award from the Center for Puerto Rican Studies at Hunter College and was designated a Distinguished Latina by El Diario/La Prensa.

This Hurricane Season, Puerto Ricans Are Imagining a Sustainable Future

Puerto Rican movements are rebuilding their island in a way that not only enhances climate resilience, but also reclaims their political power.

By , . Foreign Policy In Focus

Nine months after Hurricane Maria made landfall in Puerto Rico, the Caribbean island faces another potentially devastating hurricane season, while much of its infrastructure and land still remain in tatters.

The category-5 hurricane that ripped through the Caribbean last fall not only caused nearly 5,000 deaths, but also exposed the fragility of the island’s social, political, and economic underpinnings. The truth behind Maria’s devastation and the United States’ laggard response to the hurricane lies in centuries of colonial exploitation — first by Spain and then by the United States — and in its perpetual subjugation to the whims of American elite.

There is little that distinguishes Puerto Rico from an American colony. Since its acquisition of the island in 1898, the United States has gradually stripped Puerto Rico of any political agency through a web of legal cases, laws, and arbitrary categorizations intended to keep Puerto Rico politically weak and economically dependent on American products — and its poor, brown, “foreign” population distanced from their mainland compatriots.

Hurricane Maria exposed for the world to see what Puerto Ricans have known for centuries: that Washington treats Puerto Rico as little more than a captive market from which the U.S. extracts profits. Although Puerto Rico is an island bathed in sunlight and lashed by winds and waves, it imports 98 percent of its energy from American fossil fuel companies. And despite its fertile soil and lush tropical landscape, Puerto Rico buys around 90 percent of its food from U.S. agribusiness companies.

When Hurricane Maria hit Puerto Rico last September, it eviscerated fields of monocrops and shattered Puerto Rico’s already derelict electric grid. Many of the almost 5,000 deaths that resulted from Maria were due not to Maria’s whipping winds or flash flooding, but to the mass power outages and food shortages that ensued, a result of the government’s closing of hospitals and neglect of the electric grid necessitated by U.S.-imposed austerity measures.

Despite its catastrophic impacts, Hurricane Maria provides a kind of tabula rasa upon which a new, economically regenerative, and politically empowered Puerto Rico can be built. Several international and local organizations are already working in Puerto Rico to transition it away from an extractive and U.S.-dependent economy towards a self-sufficient, socially just, and ecologically sound one — while at the same time enhancing local economies, reclaiming sovereignty, and boosting climate resilience.

“When Puerto Rico experienced the effects of Maria,” says Angela Adrar of the Climate Justice Alliance, “it was clear that we had a one in a lifetime opportunity to unite communities together and have a vision for a just recovery.” That vision incorporates “food sovereignty, energy democracy, self-determination, and a real justice approach…to building power.” A just recovery for Puerto Rico not only means rebuilding what Maria destroyed, but reclaiming the political and economic agency stifled by American colonialism.

Resilient Power Puerto Rico, a grassroots relief effort that began hours after Maria hit the island, promotes energy democracy in post-Maria Puerto Rico by distributing solar-powered generators to remote parts of the island. The Just Transition Alliance, Climate Justice Alliance, and Greenpeace have also sent brigades to install solar panels across the island.

Solar energy reduces the carbon emissions that fueled Maria’s intensity and makes Puerto Rico more resilient against the next climate-charged storm. A decentralized renewable energy grid — which allows solar users to plug into or remain independent of the larger grid as necessary — combats Puerto Rico’s dependence on U.S. fossil fuels. It also democratizes Puerto Rico’s energy supply, placing power (literally and metaphorically) in the hands of Puerto Ricans rather than American fossil fuel corporations.

Another aspect of Puerto Rico’s “just recovery” is food sovereignty, a movement to promote community-controlled agricultural cooperatives that grow food for local consumption and thus counter Puerto Rico’s reliance on the American food industry.

The Organizatión Boricuá de Agricultura Ecológica encourages food sovereignty through “agroecology,” a method that revives local agriculture through traditional farming methods, rather than the monoculture system put in place by American colonists.

According to Corbin Laedlein of WhyHunger, who visited the Organizatión in 2016, “food sovereignty and agroecology are grounded in an analysis of how U.S. historic and structural settler colonialism and racism have shaped and continue to manifest in the food system today.”

By rejecting the larger food system and focusing on self-sufficiency, agroecology allows Puerto Ricans to reclaim the political and economy agency the U.S. denies them. The Organizatión sends brigades that deliver seeds for community members to plant. By stimulating local production, agroecology also reduces the carbon pollution emitted from ships transporting food to Puerto Rico, and moreover acts as a local carbon sink.

As the Atlantic Ocean incubates another hurricane season, the people of Puerto Rico are rebuilding their island in a way that not only enhances climate resilience, but also reclaims their political power. The island they are creating — one that is socially just, ecologically sustainable, and politically empowered — is an inspiring model for a just, sustainable future. One that is definitively not American-made.

Puerto Rico’s American Dream is dead

The traditional American dream is that the poorer parts of this country would, sooner or later, start catching up to the richer parts. The American South, after an extreme divergence, gained on the North after World War II. But Puerto Rico never made the same leap, and in relative terms has held roughly steady since 1970.

Worse yet, the island has about $123 billion in debt and pension obligations, compared with a gross domestic product of slightly more than $100 billion, a number that is sure to fall. In the last decade, the island has lost about 9 percent of its population, including many ambitious and talented individuals. In the past 20 years, Puerto Rico’s labor force shrank by about 20 percent, with the health-care sector being especially hard hit. The population of children under 5 has fallen 37 percent since 2000, and Puerto Rico has more of its population over 60 than any U.S. state.

Hurricane Maria has produced conditions unprecedented in recent American experience. Much of the island has no fresh water and no phone service, and the status of the food supply and its accessibility is uncertain. Restoring electricity will take months, the health-care system isn’t functioning, and a major dam may yet break, causing further dangerous flooding.

Those developments will worsen the already dire long-term prospects for Puerto Rico. Tourism no longer exists after the storm, and presumably outside investment will decline in both the short and longer run, due to damaged infrastructure and the possibility that major storms are now more likely as the climate changes.

Federal aid is being mobilized, but that won’t even restore the pre-storm state, which was already fiscally insolvent. Nydia Velazquez, a representative from New York, will be requesting a one-year waiver from the Jones Act, a federal law that requires cargo shipments to Puerto Rico take place on U.S. vehicles. The act was originally intended to help the U.S. shipping industry, but it raises prices in Puerto Rico by raising costs. A one-year waiver is better than nothing, but it’s sad we cannot repeal the Jones Act altogether, or at least permanently exempt Puerto Rico. It’s a sign of how little we are willing to budge to solve what is a catastrophic problem for 3.4 million Americans.

Statehood would have been Puerto Rico’s best chance for economic growth. One of the wisest features of American policy after the Revolution was the emphasis on rapid statehood, rather than territory status. When regions moved from territories to full-blown states, it provided a big boost to their per capita incomes. Puerto Rico never did the same, in part because its citizens voted not to, and in part because the mainland was reluctant to absorb a Hispanic territory. These days, political polarization renders statehood hard to imagine, as Puerto Rican senators likely would be Democrats.

Increasingly, it seems that many parts of the Western world might never “catch up,” including Greece, southern Italy, much of the Balkans and much of Latin America, in addition to Puerto Rico. One of the pleasing features of the 1990s, in retrospect a delusion, was the notion that proper policy and good multilateral institutions would bring most of the world into consistent, steady-state growth at a higher rate than what the wealthier countries could manage.

Sending external aid for life support is a fundamentally different endeavor than seeking to restore and then boost sustainable growth. Are we really ready to write off Puerto Rico? That this story hasn’t dominated the headlines unfortunately suggests the answer is yes. We’re looking at a future where Puerto Rico has simply ceased to be an independently viable economic unit.

In addition to the well-being of Puerto Ricans, at stake is what kind of nation the U.S. is going to be. Do we respond to major challenges, or run away from them? I expect to see American generosity toward Puerto Rico’s storm recovery, but unfortunately very little engagement with this more fundamental question.

BX3M, a film by Judith Escalona at the Havana Film Festival New York

BX3M, a film written anddirected by Judith Escalona, is in competition for the Havana Star Prize at the Havana Film Festival NY!

For Maria and Mona, graduation means fulfilling a dream. For Michael, it means dashing all hope of a better future. You either make the grade or you don’t— in academics or love— and that makes all the difference.

The film will screen Thursday, April 12 at 8:30PM––AMC Loews, West 34th Street, between 8th and 9th Avenues. See you there!

CLICK HERE TO BUY TICKETS: https://www.eventbrite.com/e/bx3m-tickets-44151114171

Puerto Rico is a changed land and the Puerto Rican people need our aid

With the two hurricanes that struck Puerto Rico in September, the island has been transformed into a paradisic wasteland. FEMA and the general federal response to the island, that has lost all electrical power and lines of communication after MARIA rolled over and just sat on it, has been exasperatingly poor. Mismanagement from FEMA and the limited deployment of the military has led to the death of people in the interior and to a majority of people with limited access to food and water. Conditions have deteriorated to such a degree that there is the fear of an outbreak of cholera. Governor Rosello is eating his words for saying that the Feds have acted appropriately. Mayor Yulin of San Juan stands out as someone who drew attention to the inadequate and inept response of FEMA. According to one news commentator, Yulin changed the way Puerto Rico is being covered. Example: While FEMA reportedly said that certain communities in the interior were unreachable, reporters and volunteer teams delivering food and water were able to arrive without much difficulty. The famed ship USNS Comfort, a floating hospital with 800 beds, and teams of doctors, has only 8 patients while people are dying for lack of access to dialysis, and other life support equipment. Now, nearly a month later, most of the country remains in darkness. What’s absurdly surreal and frustrating, the Comfort requires that people be referred by a doctor. Puerto Rico is choking on Federal red tape.

To donate check out a recent reposting of artist Nayda Collazo-Llorens recommendations on PRdream’s Facebook page: https://m.facebook.com/story.php?story_fbid=1705378302826132&id=262890787074898&_rdr

We haven’t been posting here. We have been posting about the crisis in Puerto Rico on PRdream’s Facebook page. More later.